Whether or not video games are an inherently violent medium, it is not their defining trait. The thing which distinguishes interactive media is that it responds to user input. Of course, I don’t mean for this to be some great insight – this is a very basic definition. And as it is necessarily true that a game responds to the player, simply satisfying this requirement is unsatisfactory. I contend that we should strive for more, that the most important medium-specific trait of games is that they allow players to act according to their own desires and designs.

Not every genre offers the same degree of freedom, and certain gameplay scenarios place greater or lesser emphasis on the two dimensions of liberty. In essence, positive liberty is the ability to do something and negative liberty is freedom from constraints. Some measure of both is required for a person or player to experience agency.

While it is not necessarily true that you must give up one in exchange for the other, a level is typically structured such that as positive liberty increases, negative liberty decreases. To some extent, this tradeoff is perfectly acceptable and indeed necessary for the game to remain fun – the more power a player is given, the greater the obstacle they should overcome. If you give a player a tank, increasing his positive liberty, you will want to decrease his negative liberty by imposing a greater level of external constraints in the form of more numerous and powerful enemies.

And this approach is appropriate – the goal of a level designer should not be to maximize every dimension of player liberty at all points during the game. Without enemies to overcome, an increased capacity to blow them up is irrelevant. However, these gameplay sequences typically feature further limitations to negative liberty by confining player movement. High-impact, bombastic moments – theoretically periods of greatest interest for the player – tend to unfold along narrow, predetermined paths.

Consider the typical vehicle sequence. While you have the most powerful, destructive tool in the game, your path has already been charted through a relatively restricted canyon or corridor, whereas you once had a wide open battlefield as your sandbox. Monster closets are suddenly open and shut by your unstoppable onslaught. The speed with which you tear through your enemies means that even the most dynamic, reactive AI will not get the chance to surprise you. They are presented as targets which are easy to eliminate these encounters are designed and expected to play out in a given way.

This is true even in games noted for their looser, less directed “sandbox” style of gameplay. Every Halo game, including Ensemble’s RTS, has a level where you roll through a linear encounter and blow stuff up with a really powerful tank. But because of the way these encounters are structured, you rarely get the opportunity to exercise your increased power in a meaningful way. If you successfully complete the encounter, it is because you killed what the designers intended you to kill with the weapon they wanted you to shoot in the place they expected this encounter to occur. Halo 3′s “The Ark” emphasizes the linear process of rolling through a specifically placed enemies the with sequentially triggered dialogue “Tank beats Ghost. Tank beats Hunter. Tank beats everything!”

But this is not to say these sequences can’t be or aren’t great fun. I’m sure most fans of the genre would agree that these moments effectively change pacing and elevate excitement. The Chronicles of Riddick: Escape from Butcher Bay perfectly demonstrates these sequences can be a compelling reward, as well as a salient example of inverse correlation between positive and negative liberty. As you spend the entire game trying to escape a maximum security prison, the game is structured around expansions and contractions of your freedom. And when you stage your final escape attempt, it follows the point when from a fiction and gameplay standpoint your liberty is most restricted.

After breaking out of a maximum security cryo facility, you take control of a powerful mech and mow through waves of guards on your way to the exit, firing guns, missiles, and stomping on your hapless foes. But you are walking through a narrow corridor this entire time, and from a gameplay standpoint your negative liberty is wholly undermined by this narrow pathway. But because your positive liberty is significantly higher than at any other point in the game, and by exercising this freedom you fulfill your fictional goal of freeing yourself, you feel a high degree of negative liberty even though the path you walk and the course of action you must pursue is wholly constrained. As a product of successful storytelling and the deliberate modulation of player freedoms, it nevertheless conveys the feeling of breaking free from constraints.

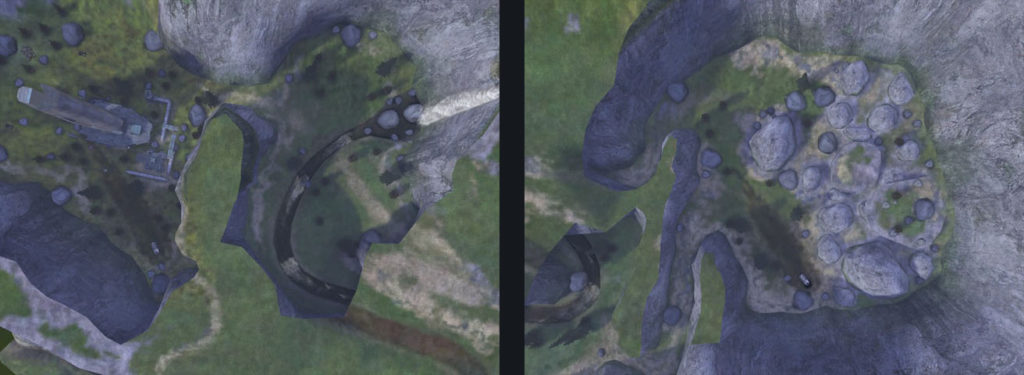

Quite like a prison, the environment has the effect of confining a player’s actions, but contrasting levels in the original Halo demonstrate that a little latitude goes a long way. While the opening sequence plays like the typical corridor shooter, once you crash land on the ringworld, encounters take place in large, nonlinear spaces, some of which have more than one entrance.

In the “Reunion Tour” chapter, you are tasked with rescuing your fellow soldiers and crewmembers. Following a tunnel that cuts through the cliff faces, you eventually arrive at a beautiful, wide open vista than beckons to your instinct for exploration. As you climb a hill in the Warthog, the terrain unfolds in every direction, leaving it up to the player as to where to take the fight. Signal flares and other signposts help you spot areas of interest, but the space cannot confine you to a particular path. And the first of these things you might notice, a crashed escape pod, has an equal chance of pointing you in one of several directions. That the three destinations might be reached in any order makes for a much more natural, much less predictable experience, but one in which the player has heightened agency.

Compared to subsequent games, the AI in the original Halo is not that sophisticated, with a limited set of behaviors whereby they pursue or flee the player en route to a firing point or hiding spot. But at the same time, the size and shape of this space make for an unpredictable and malleable encounter. As the enemies are defensively biased, and none are attacking you from the outset, there is no clear indication of which enemies to eliminate first. As the player can move in a full circle around the enemy encampment, they can attack from almost any angle or engagement distance. With a vehicle crewed by a marine gunner at your disposal, it is also possible to split your presence in the space, using it to lure or flank enemies in addition to direct confrontation.

Given the variety of tools at their disposal, and the unrestricted nature of the environment, players have an open sandbox they can reshape in an astonishing variety of ways. Between powerful long range weapons and a vehicle that not only allows you to traverse great distances quickly but coordinate deadly flanking attacks, the player has the instruments of high positive liberty. Combined with the high negative liberty of a wide open environment and defensively biased enemies, this offers a high level agency.

An intensely focused level design undermines this high degree of negative liberty. While you might engineer a desired interest curve by forcing players through a tightly scripted series of events, you run the risk of your audience awakening to the narrowness of the experience. Any time the game plays out in a particular, predetermined way, it undermines the player’s authority in favor of the designer’s authorship. When this deliberate design confines the player to the extent that he cannot pursue his own desires, you will not retain his interest but lose it more quickly.

When a game leads a player by the nose down a narrow path, then it’s undermining the ultimate potential of interactivity, whereby the user not only participates in but defines the experience. With events and encounters presented to you in a straightforward fashion, the notion that you are empowered within this world will erode. Since game narration tends to be egocentric, in that the player is a powerful central character, you are almost invariably afforded a high degree of positive liberty. You are granted power that you would not or cannot wield in real life, but the more this power is focused towards a narrow, predefined objective, the less meaningful these virtual freedoms. Without a measure of negative liberty, without being free from constraints, positive liberty is not freedom at all.

Role-playing games are a natural platform for user-defined experience, but many fall into the trap of equating freedom and choice. Fable and Mass Effect thrive on the notion that you can define your character through a series of choices but these binary options are actually another form of constraint. The presence of two choices provides the illusion of freedom, when in fact it undermines agency. Having to make a life and death decision between two of the Normandy’s crew members quite like having no choice at all.

The Elder Scrolls provides a preferable alternative, whereby the player is offered widely divergent avenues to which they may gravitate, which cause the virtual world shift in line with the actions the player pursues. “And sometimes that just creates a little bit of a mess,” explains Todd Howard. “You know, the player does this, this, and this we didn’t expect. But we think that percentage of time that something gets messy or weird, the payoff – because it lets you do all this stuff – is greater. So we give up control to the player.”

For some, less directed designs will cause complaints of confusion or boredom. But it’s more important to give the player control over the experience than to make sure that all players are entertained at all times. Even as developers make games for wider and wider audiences, or seek to emulate linear storytelling methods, they must preserve and privilege the medium specific traits of freedom and agency. While a game cannot exist unless a designer establishes some sort of starting point, and possibly an end goal, these elements are like the key frames of animation in that the life and magic comes from what happens in between.

Games are important because they can allow you to experience a wide range of events that one person, individual and mortal, could never undergo in the course of his lifetime. They allow people to explore freedoms and enjoy abilities that they do not or cannot have in life. But every moment you spend in a virtual world is one less you have in reality. And quite apart from a player’s in-game liberty, we ought to ensure that games do not infringe upon life more than they must. Passion, not compulsion, should be the reason to play games. We should want not to expel boredom, but feel freedom. Each moment should have meaning enough to justify a player’s investment and the sacrifice he makes to play it.